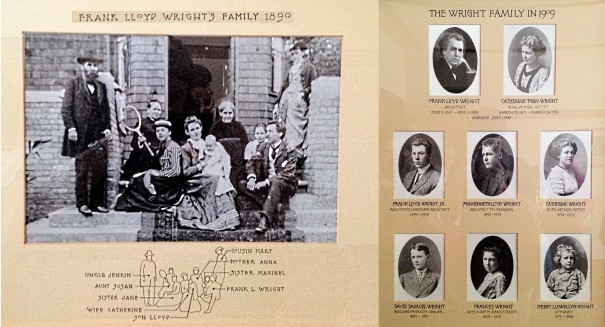

The Frank Lloyd Wright Home & Studio in Oak Park, Ill., is a microcosm of the prolific designer’s ever-evolving architectural aesthetic. It’s an expression of his early formative years, and through a series of additions, it embodies the changes that his philosophy and style underwent during the twenty year span (1889-1909) that he lived in the home.

Wright moved to Chicago in 1887, and after two brief stints with smaller architectural firms, he landed an apprenticeship with the well-known firm of Adler & Sullivan. Almost immediately, Wright made an impression on his mentor, Louis Sullivan, who soon took the young phenom under his wing. Upon signing a five-year employment contract with the firm in early 1889, Wright approached Sullivan for a $5,000 loan to build a home for he and his wife, Catherine, and the family they planned to raise in the Oak Park suburb of Chicago.

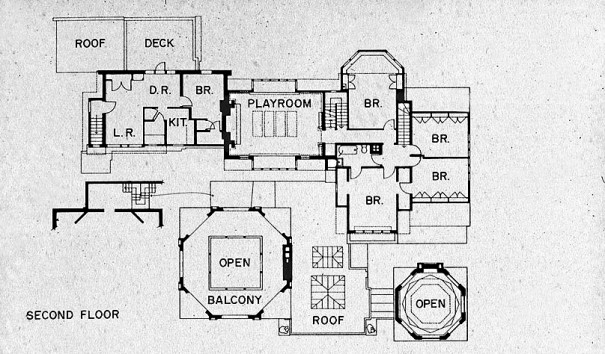

The original 1889 design was a modest, three-bedroom Shingle Style home with a conventional gabled façade (above). Wright would father four children over the next six years, and in 1895, he expanded the home by converting the existing kitchen into a dining room and building a new kitchen onto the back of the home. On the second floor, he added an elaborate childrens’ playroom with two symmetric oriel windows (one can be seen below, foreground), and expanded the nursery over the aforementioned dining room (below, left).

Unlike many of his later Prairie Style designs, the front door of the home (below) is in the traditional place and easy to find as you approach the home. A wrap-around front porch sits beneath the home’s massive triangular gable while a tapered brick wall surrounds the entry and provides private outdoor space where the growing Wright family often gathered.

Upon entering the home, the home’s main staircase spills into the entryway in front of you (below, right), as the living room beckons you to the left. Once in the living room, a cozy inglenook sits off to your right (below, left). Wright believed that the hearth was the heart of the the home, and a quote etched into the panel above the sunrise fireplace reads, “Truth is Life. Good friends, around these hearth stones, speak no evil word of any creature.”

The living room (below) is actually the only room in the house that remains today as it was in the original 1889 home. Two generously-sized bay windows, provide ample natural light, as well as seating and storage beneath. The two chairs pictured below are original.

The original dining room (below) became Wright’s study after the 1895 renovation.

The present dining room (below) houses the family’s original dining table and chairs. The room is quite spacious, but the high-backed chairs, designed by Wright, create a “room within a room” and a more intimate dining experience overall. Windows are placed high on the far wall, so as to allow for natural light, yet still retain a sense of privacy.

After the 1895 renovation, the home still had just three bedrooms, and one of them was primarily being used as a nursery. By 1900, the Wright family had grown to five children, with a sixth to be born a few years later, and the children’s sleeping arrangements were constantly in flux.

While in their infancy, the children spent much of their time in the nursery (below), nicknamed Catherine’s Dayroom. The three-sided far end of the room and window panel above were added when the dining room below it was expanded in 1895. The crib (below, center) is a genuine Wright family heirloom, and actually dates back to Wright’s wife’s family [Tobin], circa 1850. Each of the six Wright children slept in it as infants.

All of the kids eventually slept in one large room that was divided in half by a partition wall. The girls slept on one side (below, left), while the boys slept on the other (below, right).

Wright and his wife Catherine slept in the highly stylized master bedroom below (left). With its vaulted ceiling, hanging pendant lights, and murals, the room was unique for its time. Painted by Wright-collaborator, Orlando Giannini, the murals at either end of the room depict a quasi- Native American/Egyptian motif that the pendant lights (designed by Wright) were meant to compliment. The adjoining bathroom (below, right) is the only one in the home and, therefore, was shared by all family members. Its horizontally banded oak panels invoke a tranquil Japanese influence, while a small window tucked into an otherwise useless space provides light, privacy and ventilation.

A short walk down a long, narrow, low-ceiling hallway leads you to the jewel of the home, the Childrens’ Playroom (below). This “compression and expansion” technique is one that Wright would use throughout his career to divide spaces and emphasize drama. And what a dramatic space it is! The first thing that catches your eye is the large graceful mural above the fireplace (again painted by Orlando Giannini) that depicts a scene from one of the childrens’ favorite stories, Arabian Nights. Looking back toward the hallway, you see an upper gallery that the children used as a play area and stage (below, right).

In the middle of the massively arcing ceiling is an equally massive skylight with four intricately-cut grille panels (below) that screen the harsh mid-day sun. The room’s grand piano (above, right) is recessed into the wall and extends into the stairway behind. As you walk down stairs, you actually walk right beneath it. It’s quite an ingenious use of space.

On either side of the room is one of the aforementioned oriel windows (below) that were specifically scaled for young children. One can only imagine how much fun the Wright children had in this amazingly well-conceived and incredibly unique playroom.

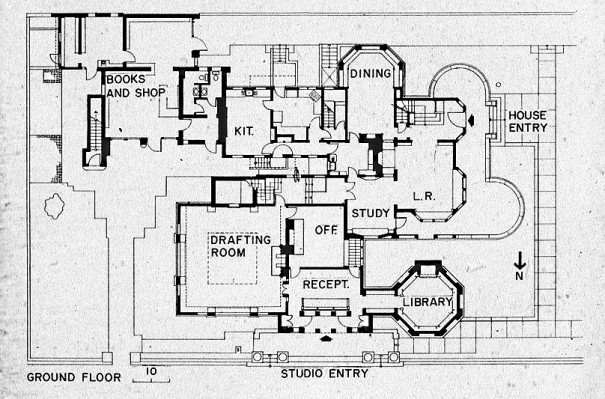

By 1898, Wright had long since left Adler & Sullivan and branched out on his own. He had been renting office space in a few different downtown Chicago buildings since 1893, including the Schiller and Steinway Hall buildings, but by the late 1890’s, most of his architectural commissions were coming from clients in his home neighborhood of Oak Park. He decided that instead of commuting to downtown Chicago everyday, it would make sense to add on to his own home and move his design studios there. The floor plans below show what the home looked like following the studio addition that took place in 1898.

In the first floor plan (above), everything seen below the “Study” (in the middle of the image) was part of the 1898 studio addition. Wright had been experimenting with a multitude of new design ideas and the studio addition was a radical departure from the rest of the home’s shingle style exterior. He used the studio addition as a testing ground for some of his early Prairie Style motifs that he would develop further in the coming years.

The main part of the addition included the entry/reception room and the drafting room, pictured below. Consistent with his later designs, Wright hid the doorway to the studio, forcing visitors to assess the building as-a-whole before proceeding inside. This little hide-and-seek game would become omnipresent in many of Wright’s future designs.

The door – or doors, there are two – are secluded at either end of a narrow space behind these four stork-themed capitals (below). Aside from the storks (representing fertility and wisdom), the capitals also depict a tree of life (representing nature), books (knowledge), as well as various architectural scrolls. In the foreground is an imposing plaque bearing Wright’s name and his design logo. This is a reproduction; the original is in a museum.

Once inside, the reception area (below) has seating for visitors and a large counter space used for viewing drawings and blueprints. Another skylight allows light, filtered by three beautiful art glass windows, to gracefully pour in from above.

Transitioning into the drafting room, at first glance (below), the room appears to be a rather straightforward work space, with a row of drafting tables flanking each side of the room…

…But as you make your way into the center of the room and look upwards, you’re dwarfed by the atrium’s soaring ceiling (below). An octagonal second floor mezzanine surrounds the atrium and is cleverly supported by a network of chains, alleviating the need for structural columns, and thereby providing the space with unencumbered beauty.

Among those who worked under Wright in Oak Park – and were part of what became known as the Prairie School Movement – were such notable designers as: Marion Lucy Mahony, Francis Barry Byrne, and William Eugene Drummond, all of whom went on to have long and successful architecture careers of their own. Within these walls, well over 100 Wright designs were born, including the Frederick C. Robie House (in Chicago), the Darwin D. Martin House and the Larkin Building (both in Buffalo, NY).

Wright’s own office (below) is tucked around the corner and separated from the drafting room by another large sunrise fireplace. More art glass is found here filtering light from another large skylight and a three-panel window.

The final part of the 1898 studio addition is the library (below). It comprises the northwest corner of the building and continues the octagonal theme that we saw earlier in the Drafting Room, although smaller in this case. A cantilevered horizontal roof unifies the rectilinear look of other aspects of the northern façade.

Inside, the Library is a real visual treat. The octagonal pattern is not only repeated, but rotated multiple times. Beginning at the ceiling, notice how the octagon is rotated above, and again below, the windows. When seated at the low-slung table below, where Wright would meet and discuss business with clients, the vertical space of the room is emphasized.

Of all the home tours I’ve been on, the Frank Lloyd Wright Home & Studio tour ranks among the best. Not just because the building itself is so remarkable, but because you get to see every inch of the house in one comprehensive tour. I would highly suggest this tour as part of your next trip to Chicago, and while you’re at it, be sure to check out the dozens of other homes that Wright designed in Oak Park and the adjacent River Forest neighborhood. And don’t forget to visit the Robie House on the University of Chicago campus, as well as countless other Chicago bungalow neighborhoods!

5 comments

roger mull says:

Aug 12, 2013

love the Bungalow style home

Arlene lowe says:

Dec 26, 2013

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home & Studio looks really awesome. Every part of the house is designed well which attracts everyone.

Kyla Clay says:

May 4, 2016

Just a note, the playroom mural was actually painted by a colleague of Wright’s, Charles Corwin. Not Orlando Giannini. 🙂

http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/homeandstudio

Kyla says:

May 4, 2016

Just a note, the playroom mural was actually painted by a colleague of Wright’s, Charles Corwin. Not Orlando Giannini. smile emoticon

http://www.flwright.org/researchexplore/homeandstudio

Jim Hisler says:

Mar 13, 2021

Hello. My name is Jim Hisler. During most of 2011, I volunteered at FLWHS and enjoyed leading many tours.

I am returning to Chicago in April to stay. Please let me know if you need guides for Spring/Summer; I would,

of course, need to retrain.